After the failure at the polls, much attention from socialists and trade unionists has fallen upon the possibilities of working class political representation. While some talk of ‘reclaiming’ the Labour Party for the workers movement, others feel this party has had it’s day, and a replacement is needed. The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) can in many ways be seen as the springboard for the latest such attempt – coming on the heels of past attempts, such as Arthur Scargil’s Socialist Labour Party.

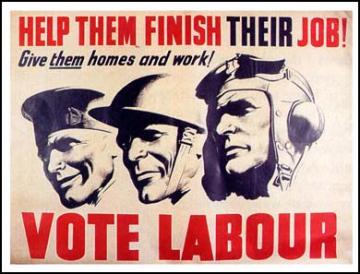

Labour themselves resorted to ‘class war’ rhetoric in a supposed ‘core vote’ strategy during the election campaign. This is not of course a new idea. The Labour Party was founded in the early 20th century, and subsequently set about supporting imperialist wars and breaking strikes. So why after a century of failure is the idea of a workers’ party stubbornly refusing to die?

Red-tinted spectacles

Much of the appeal of the idea lies in a certain mythology about the Labour Party. They were, so the story goes, once genuinely on the side of the working class, but now, sadly, they’re not. So, according to this story, we now need a new workers party that really does represent us. As the RMT put it in a recent conference on ‘The Crisis in Working Class Political Representation’, their aim is “harnessing rank and file anger at attacks on jobs, pay, conditions and pensions into a co-ordinated political voice.”

The ‘Campaign for a New Workers Party’, a campaign of the Socialist Party, summarises itself: “If you think all the big political parties are the same – you’re right! The bosses have got three parties – isn’t it about time we had one of our own?” Before dealing with the problems of working class political representation in its own right, it’s worth debunking some of the mythology surrounding the Labour Party. This should help make clear that criticisms of party politics are not simply anarchist dogma, but drawn are rooted in bitter working class experiences that today’s militants should heed before setting off down the same well-trodden path.

From union representation to political representation

The Labour Party was founded in 1906 with the election of 29 MPs from the Labour Representation Committee, made up mainly of Trade Union bureaucrats with support from socialist groups. The immediate trigger for this was the ruling in the 1901 Taff Vale case which had made Trade Unions liable for loss of profits during strike action. The ruling was reversed by the Liberal-Labour supported Trades Disputes Act in 1906. However a mere four years later, historian Bob Holton writes that for many militant workers “the clear-cut non-parliamentary message of syndicalism proved more attractive, since it avoided the problems of political incorporation which increasingly beset the Labour Party in parliament”. The ‘Syndicalist Revolt’ of 1910-1914 saw a rising wave of industrial unrest as discontent with both union bureaucracies and Labour MPs spread amongst the more combative sections of the working class.

Having opted to support the First World War – and thus support sending millions or workers to die for their bosses – Labour’s first taste of real political power came during the war when they were rewarded with a part in a coalition government. They further underlined their ruling class politics by opposing the upsurge in workers’ militancy that wartime austerity helped ferment. As strikes spread, particularly on ‘Red Clydeside’, Labour responded by helping break them. As socialists and anarchists were imprisoned for refusing to sign up, Labour rallied to “Win the War” and sought to expel pacifist/anti-war elements from within its ranks.

The first two labour governments were no better. The Subversion group writes that “J H Thomas, Union leader and MP, was appointed to the Colonial Office. He introduced himself to his departmental heads with the statement: “I’m here to see there is no mucking about with the British Empire.”” Their first term only lasted 10 months, but on top of their enthusiastic imperialism they managed to oppose strikes by dockers, London tramway workers and railwaymen, invoking the 1920 Emergency Powers Act against the latter two and threatening to declare a state of emergency. In 1926 and back in opposition the party feared the general strike would lead to revolutionary events and scrambled to prevent it. Three years later they again formed a minority government. Promising to lower rampant unemployment, within two years it had more than doubled.

So from its very inception ‘working class political representation’ acted consistently like every other capitalist political party: at best impotently overseeing the misery caused by the movement of the capitalist economy, and at worst actively smashing working class self-organisation. In other words, for the bosses and against the working class. But aren’t we being unfair? We’ve not even mentioned Labour’s ‘greatest achievement’…

The welfare state – ‘Labour’s great achievement’

The single-most cited ‘benefit’ of so-called workers’ parties is the foundation of the welfare state in 1948. Universal healthcare and unemployed benefits certainly represent gains for the working class insofar as they are paid for by the bosses. But why were they introduced? The foundations for the welfare state were laid by the 1942 cross-party Beveridge Report, which recommended the measures implemented by Clement Attlee’s Labour government when they came to power in 1945. Beveridge himself was a rather unsavoury character, who had supported benefits so long as the “unemployable” were sterilised and stripped of civil rights, but it is the motives behind the adoption of the report’s proposals which are most revealing.

Wary of the worldwide revolutionary wave which followed the end of the First World War, there was a cross-party consensus that war-weary workers would need to be given incentives not to turn their discontent (or even their guns) on the government. The Tory Quintin Hogg summed up the prevailing mood in 1943 when he said “we must give them reform or they will give us revolution.” The welfare state fitted that bill, and the wave of post-war mass squatting of disused military bases by homeless workers convinced the ruling class of the reality of the threat.

But even this self-interest was not enough. The second strand of the cross-party consensus was that a welfare state served ‘the national interest’ of building profitable British industry by shifting the cost of maintaining the workforce from private businesses onto the state via national insurance payments deducted from workers’ wages (whether or not it actually did so is not a question to be taken up here; successful post-war wage struggles probably shifted the cost onto the bosses, which is why they came to hate the welfare state).

Giving up the pretence

It is ironic that ‘Labour’s greatest achievement’ was supported by a cross-party consensus which would have almost certainly seen the recommendations of the Beveridge report implemented regardless of who won the 1945 general election. Certainly, the fact it was ‘political representatives of the working class’ overseeing its introduction seems of little importance when they were implementing ruling class consensus. In any event, without the tangible threat of working class unrest, that consensus would never have been acted on. So let us fast-forward to the 1970s to see how ‘working class political representation’ dealt with significant working class struggle.

The 70’s was a decade of major industrial unrest, as inflation hit double figures and wages failed to keep pace with the spiralling cost of living. Legislation limiting pay rises was proving unpopular and unenforceable in the face of widespread unofficial action outside of the control of the TUC unions and their Labour Party chums. Consequently, Labour turned to the TUC to implement ‘voluntary’ pay freezes, with partial success as unions policed their angry membership. The crisis deepened and by 1976 Britain went to the IMF for emergency assistance. This came with the usual strings attached – austerity measures and public service cuts which the Labour government was only too keen to implement. The confrontation between the working class and their ‘political representatives’ came to a head in 1978 – 79 in the so-called winter of discontent. As strike waves brought the country to a standstill Labour became unelectable and wouldn’t taste power again until their ‘New Labour’ rebranding, having jettisoned any pretence of advancing working class interests (a claim anyhow thoroughly discredited by their record in office and in opposition.)

Representation or self-organisation?

Discussing the triumph of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution and the counter-revolutionary practice of Social Democrats everywhere, Guy Debord once wrote that “the representation of the working class radically opposes itself to the working class.” As we have seen, from its very beginnings the political representation of the working class has never served the working class. Thus, the whole basis of the argument for a new workers party is undermined. But it is not just political representation which opposes itself to the working class, the same is also true of economic representation – the masters of which are the trade union bureaucracies.

It matters not if a representative was once a salt of the earth militant; the very practice of representation separates the representative from the represented. Representation is the act by which the many abdicate their power to a privileged few, is it any surprise that those few then act in defence of their privilege? This process claims even the most well-intentioned working class militants. For instance, historian of anarchism John Quail writes that:

“In 1912 John Turner became president of the [Shop Assistants] Union. Although he called himself an anarchist until he died it did not show itself in his union activities. Heartbreaking experience as it might have been, the small union before 1898 had been anarchistic, that after 1898 was no different to the other ‘new’ unions in either power distribution or policy (…) The executive of the union was being seen in some quarters as a bureaucratic interference with local militancy and initiative. And complaints were to grow. By 1909 Turner was being accused from one quarter of playing the role of “one of the most blatant reactionaries with which the Trades Union movement was ever cursed”.”

With this in mind, it’s no surprise to hear bureaucrat Bob Crow’s RMT declaring the desire to “harness rank and file anger”. Today’s militant workers are right to look beyond trade unionism towards political objectives of social change. They’re also right to reject the existing parties as offering nothing to the working class. But history shows it would be a mistake to place ourselves in a “harness” that serves only to catapult self-interested bureaucrats into power in our name. Workers are strongest when they take direct action themselves and threaten to spread it– as shown by two of the most successful struggles of the last year; the Visteon occupations and the refinery wildcats. Abdicating power whether to trade union bureaucrats or politicians can only ever weaken the confidence and capacity of the working class to struggle in our own interests. It is no coincidence that all the parties in power are the bosses’ parties. Every politician joins the ruling class – by definition. A ‘workers party’ is therefore a contradiction in terms, as their anti-working class history when in power amply demonstrates.

Comments

OK, so you've pointed out the

As the article mentions,