In the late 1990s, plans to outsource track maintenance on the London Underground were being pushed through by the government. Workers at one depot responded by forming a new workplace group, both inside and outside the existing union, the RMT. This pamphlet charts the highs and lows of the Workmates collective, highlighting their successes and failures, their radically democratic organising method and their creative forms of direct action. We hope it can provide an inspiration to other workers frustrated with the limits of the existing workplace organisations.

A copy of the pamphlet costs £2 including postage and packaging (to UK, please get in touch for international or bulk orders).

Introduction

In the late 1990s, track maintenance workers on the London Underground faced being outsourced to a private contractor under a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) scheme. The aim of the PPP was to cut costs by introducing competitive tendering by private contractors to do the work which had previously been done in-house. This casualisation would undercut the hard-won terms and conditions of London Underground staff and replace relative job security with the temporary, insecure employment that has become so widespread under the mantra of the ‘flexible labour market’.

London Underground workers were mainly organised with the Rail, Maritime and Transport union (RMT). However third-party contractors and casual staff were typically not unionised. Andy, an RMT rep and anarchist, sought to utilise anarcho-syndicalist tactics like mass meetings and on-the-job direct action to overcome divisions between union and non-union workers, and build resistance to the increasing privatisation and outsourcing on the London Underground, itself a tactic used to divide and rule the workforce.

This led to the founding of the Workmates collective in late 1998/early 1999, a workplace group based out of a London maintenance depot. Workmates was open to all workers regardless of union membership, and sought to organise action on the shop floor, controlled by the workers themselves. The Workmates collective was fully functioning with a delegate council structure for around 18 months into mid-2000. During this time they organised numerous actions with varying degrees of success until staff turnover and the strain on a small number of core activists took its toll. Despite this, the culture of canteen mass meetings has continued for the last decade, and workplace meetings open to all workers are ongoing as of 2011.

The Workmates experience touches on many issues of interest to workplace activists. In an age of austerity, the threat of outsourcing and casualisation remains a big issue for both private and public sector workers, the poor conditions of the former being used to attack the conditions of the latter. Also, the question of how workplace militants relate to the existing trade unions is important: with the official trade unions showing themselves both unable and unwilling to fight for workers, how can workers organise to defend themselves? Moreover, how do those of us committed to workplace organisation based on direct action and grassroots control, rather than representation and a reliance on restrictive industrial relations legisation, relate to the bureaucratic trade unions? Can a militant worker achieve anything outside of the framework set by the unions? This account, based on discussions with Andy, touches on these, and other, issues relating to workplace organising in the new era of 'flexible' employment.

The Solidarity Federation is not publishing this pamphlet because Workmates is a definitive blueprint for workplace organisation. Certainly, there are many aspects of it which we think are inspiring and point to the principles which workplace organisation should be based on. However, more importantly, we hope the experiences recounted here can stimulate discussion and provoke serious thought among workplace activists about how we can organise in our workplaces on the basis of unmediated direct action. That is, action organised by workers themselves without the need for union officials or adherence to the industrial relations laws which all-but outlaw effective action and class solidarity.

Privatisation and casualisation

In the early 1990s, London Underground introduced its ‘Company Plan’. The plan ‘streamlined’ workers' terms and conditions, got rid of some established perks and changed the industrial relations framework. Crucially, it also led to a recruitment freeze, with new staff requirements being brought in as outsourced contractors. These measures were clearly aimed at making the company more attractive to private capital by bringing it in line with private sector norms. The RMT failed to put up a fight against the Company Plan.

This was followed in 1998 by the announcement of the intention to privatise London Underground infrastructure via a Public Private Partnership (PPP). This was the government’s idea of splitting off the trains and stations from the infrastructure and maintenance of the track, signals and everything else. When private contract companies were invited to put in tenders in 1998, that’s when the RMT started to resist it. However, this was largely a reaction by the union to anger from RMT members over their union's poor showing in the Company Plan.

This is quite strikingly demonstrated by comparing the bold claims made by Metronet when they took over with what actually happened. They had promised upgrades to 35 stations, but by the time they entered administration on 2007 they had only delivered 14. Stations budgeted at £2m came in at £7.5m, 375% of the initial cost (when the low cost of ‘private sector efficiency’ was one of the main reasons for privatisation in the first place). By November 2006, only 65% of scheduled track renewal had been achieved. On top of this chronic inefficiency, Metronet had already raised eyebrows by turning a £1m a week profit in the first year of its operation.

When the consortium entered administration in 2007, the five private backers put up £70m each. The state was forced to provide a £1.7bn bailout in order to take infrastructure maintenance back in-house. Of this, large bonuses were pocketed by at least five departing directors, although the amounts were not disclosed due to ‘commercial confidentiality’.

Before Metronet was taken back in-house by Transport for London, they had two-thirds of the lines on the London Underground, with another private firm Tube Lines having the remaining Jubilee, Northern and Piccadilly lines. They employed a core staff directly, but used contractors to make up the numbers. This allowed them to increase the workforce when the workload was high and reduce it when it was lower, keeping labour costs down. This is similar to the outsourcing seen elsewhere, and in fact early on the depot doing heavy works was called ‘TrackForce’ as a direct copy of the Royal Mail’s ParcelForce, which was privatised to handle the heavy mail side of the postal service.

These types of firms are then made to compete with each other, creating a race to the bottom to win the contract by showing they can do it for the cheapest price.

“So in the track function there are several separate companies they use, and these companies are always competing against each other. And how they win bids is by cutting off staff so they can keep the costs low. So there’s only a few of us who work directly for London Underground or Metronet, the rest are contractors.”

This also created a web of interlinked companies that made it all-but impossible to identify who the actual employer was. Technically, most contractors were self-employed, and this completely ruled out any lawful industrial dispute since there was legally no employer to enter dispute with. Andy explains the difficulties:

“So you’ve got all these companies, and they’re all the same, they’re all just a bunch of parasites, who aren’t even needed. But it enables London Underground to offload responsibility onto these middlemen. But the thing is, these guys aren’t even employed by these companies – they are self employed, and these companies are agencies that find them work. They get their wages paid by other companies, accountancy firms. And some of these firms are actually owned by the managers in the agencies. So what happens is if one of these guys gets sacked, and you think they’ve been unfairly dismissed, and you write to the contractor, they say “we don’t employ Joe Bloggs, we just provide him with work, he works for a different company.” But then when you go to the other company, they say “we don’t employ him, we’re an accountancy firm, we just sort out his wages”. So they are caught between them like a ping pong ball. And you can never get to the bottom of who their employer is. It’s a set up basically, to deny them any employment rights, and have no way of addressing any grievances whatsoever. So that’s how they’re employed and that’s how they operate, it’s appalling.”

This ability to deny workers even the limited legal rights they do have is one of the main attractions of casualisation to employers. But as well as undermining income security and denying employment rights to workers, such casualisation also undermines the traditional model of trade unionism, based on being able to represent workers within the framework of industrial relations legislation.

Whither the union?

The Company Plan of the early 1990s, which prepared the ground for further privatisation, was not strongly resisted by the RMT. When private contract companies were invited to put in tenders in 1998, that’s when the RMT started to resist it. However, this was largely a reaction of the union to anger from RMT members over their union's poor showing in a previous dispute, the Company Plan. Andy comments:

“The RMT really fucked up with the Company Plan. They were pushed into doing something about PPP by the rank-and-file militancy and a feeling they had ‘sold out’ with the Company Plan. Fortunately we had people in our depot who’d been through the whole Company Plan in 1992 and had decided we weren’t going to let this happen to us again, so this time there was a whole different spirit.”

At the time, there were around 100 full-time staff working for London Underground doing track maintenance. For approximately two years there had also been around 200 agency staff working with them, who worked for a company called Morsons. London Underground staff were mostly in the RMT, but the contractors were non-union and were hired and fired according to work fluctuations. Andy recalls that they “all worked together, all knew each other, and had good friendships.” Under pressure from the membership, the RMT was gearing up for strike action against privatisation. However, many RMT members were suspicious of the non-union contract staff.

“There was a lot of doubt as to whether or not these guys [contractors] would break the strike. A lot of people thought they would, and so didn’t want them in the meetings we were having in the canteen to discuss the coming dispute.”

Andy and others argued against this, saying permanent and casual workers needed to stand together if the strikes were going to be effective.

“Some of us pointed out that we’ve got to get everyone involved. Bob Crow [then assistant general secretary of the RMT] came along to one, and people had not taken our view, and they approached him and said they didn’t want the contractors in this. And credit to him, he independently had the same line as us, that we’re against people in suits, not people in overalls to put it simplistically. So they stayed in the meeting.”

This was far from an ideal resolution since the matter was settled by the authority of a union official rather than by workers in the depot winning their co-workers round. However, the all-worker meetings were the start of what was to become Workmates.

From official strikes to unofficial Workmates

As the first one-day strikes approached, some contractors started to approach RMT members and reassure them they wouldn’t be crossing picket lines. The contractors were drawn from a wide area, with some travelling down to London from Wales every night for the work. It turned out that amongst them were some former miners from Doncaster and Kent who’d been through the bitter 1984/5 miners' strike. One had even been at the British Steel coking plant at Orgreave and had been part of the mass pickets by miners and the infamous battle with the police as they tried to picket out the plant.

“Just through their basic working class principles, they started explaining to other contractors that you don’t break their strike. This was spontaneous amongst the contractors that they adopted this line and were getting each other on board with this.”

“ It was a solid strike all over London, and when we went back to work, I was able to point out to the detractors that these guys do deserve to be involved in all our meetings and were good comrades – and this won the argument, especially as some of the permanent staff scabbed.”

Subsequently the idea of some kind of workplace organisation pulling together union and non-union workers began to take shape. Due to the outsourcing, the contractors were technically self-employed and thus did not have employment rights as workers. Since the RMT operated under that legal framework, there wasn’t much it could do for them and neither was there much interest amongst the contractors in joining. An idea was then had to form a group that was interdependent on the RMT – not totally in it, and not totally independent – which could benefit the contract workers while giving the group itself a bit more of an independent identity. This idea would become, 'Workmates':

“Obviously, what we were was workmates, and so that’s the name that immediately came to me. I put that forward as a name and we agreed and we got cards and badges made up, and for all the literature we used to advertise meetings and stuff like that we used the name ‘Workmates’.”

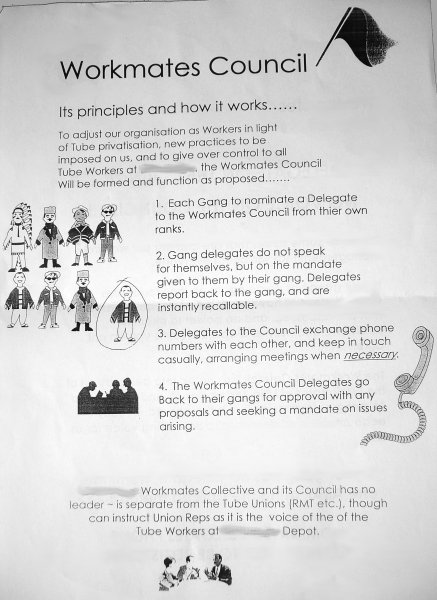

Workmates was not a parallel union, certainly in any conventional sense. Rather it was a democratic means of organising. There were no membership dues and far from seeking to negotiate with management it kept a low profile, organising semi-covertly and leaving rep work to the RMT. ACAS (Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service) guidelines stated that union reps should have the ability to report back to their membership after consultations with management. So when Workmates wanted to hold a meeting, they’d get an RMT rep to go and ‘consult’ with management ‘over an issue’, and open up the subsequent ‘report back’ to the non-union contractors too. This allowed Workmates to hold regular mass meetings at work and on work time, whilst keeping management out.

The delegate council

Unlike the RMT which it organised in parallel to, Workmates was organised according to anarcho-syndicalist principles. Specifically, there was an emphasis on workers’ control, with all decisions being taken by a show of hands in the mass meetings. In keeping with this, RMT reps began to act as delegates – taking a mandate they were accountable for from the mass meetings.

“They weren’t threatened by it – the union leadership and machinery had so much on their hands that I think they were quite in favour of it really at the time, because we were organising. Also, because we were getting contractors involved in strike action who weren’t in the union and were only indirectly affected by privatisation, it almost spread militancy across all grades on London Underground – for example it was referred to often that ‘even contractors were striking against privatisation’. We were never opposed by the RMT. They didn’t support it, but they did nothing to get in the way – just ignored it mostly, they referred to it when it suited their purposes to shore up strength in other areas.”

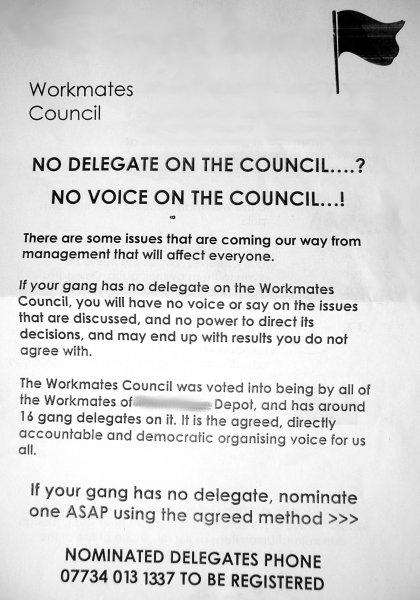

But Workmates wasn’t simply about making union reps democratically accountable, or extending RMT representation to non-members. The next step was to set up a delegate council. Not everything could be organised openly through the mass meetings as there were always management spies willing to grass up their co-workers for brownie points. Some may even have been given bonuses or perks for information, although this was hard to prove. This meant some things couldn’t be discussed openly and some people didn’t want to raise grievances in case word got back to management that they were a troublemaker. The idea with the delegate council was that each ‘gang’ of 8-16 workers would elect a delegate, and the delegates could then meet and report back to their gangs. In this way issues could be raised confidentially and plans could be made democratically without the details getting back to management.

On the whole, it was the non-union contract workers who took hold of this system, as they didn’t have the RMT organisation to use. Workers would elect a delegate from their gang to go to the delegate council. These gang groupings were flexible; they could be the group people you worked with, the people you travelled in the minibus with or however you felt it to be. These gangs would nominate someone to the delegate council and this person would be given a clear mandate to bring to the council and would also report back to their gang. The consensus from all the delegates from the gangs would then be debated and decisions would be made collectively.

The mass meetings carried on, and most of the decisions were made there, out in the open. But some things would be taken to the council from the mass meetings – there’d be a delegates meeting, delegates would take decisions back to their gangs and see what the gangs thought, then bring the council back together and see what the decision was. At the peak, about 60% of the gangs were sending delegates to the council. This partly reflected the fact the directly employed staff could use the RMT for individual grievances, whereas the contractors didn’t have this option and had to try and sort things out collectively themselves. Andy says:

“ Pretty much everyone working in the section were involved in the mass meetings, but only 16 out of a potential 25 gangs elected someone to the council. This wasn’t for want of trying – but you’re never going to get it to 100%.”

There wasn’t much in the way of hostility towards the council, it was more that some of the workers either didn’t see a reason to participate or they were happy to let the RMT handle grievances. Over time full time LUL staff members were shamed into taking part in strike action by the fact that even the non-union contractors didn’t scab, and some even manned picket lines in later disputes.

Job-and-Knock

The delegate council was in operation for about 18 months at the peak of the anti-privatisation struggle in 1999-2001. While the mass meetings were held regularly, the delegate council only met when it needed to, such as when management tried to introduce a new working practice. Aside from the PPP, several issues were tackled. The biggest was management’s attempts to end the ‘job-and-knock’ system. Under this system, work started at 11pm and workers were out on the track from half-midnight until the job was done. This could sometimes be as early as 2am or as late as 5:30, to be back in the depot by the end of the shift at 6am.

Custom and practice was for workers to knock off when the night’s work was done, hence ‘job-and-knock’. Management decided this was out of line with private sector norms, and decreed that even if the night's scheduled work was complete, workers should return to their depot and sit there until 6:30am. As well as being completely pointless, it proved hugely unpopular. Andy says “It was just them stamping their authority on us. And also the general manager was doing a business dissertation at the time, and was using us as a guinea pig, as a case study.” Workers held a mass meeting to discuss the change, and the next shift was due to call the delegate council together with views from the mass meeting.

However, the workers’ anger was such that the delegate council was actually sidelined by spontaneous action from the workers. The workforce just immediately started taking action against management on the same shift that had the mass meeting. So the delegate council became irrelevant to the struggle, and the mass meeting did it really. And from there onwards it carried on with its own momentum.

The delegate council met half-way through the action, but concluded that everything was going fine and that there weren’t any issues people had felt unable to express in the mass meeting. The action workers took was essentially an unofficial work to rule. Due to the potentially dangerous nature of the work, out on the underground tracks in the night, there were numerous rules and regulations which if followed to the letter virtually brought work to a standstill.

One particularly imaginative direct action was the ‘piss strike’. One of the health and safety regulations stated that on the tracks, all workers must at all times be accompanied by a ‘Protection Master’- a member of the workforce trained to provide safety from trains and traction current. This meant each gang tended to have just the one Protection Master, as management didn’t want to waste money training up any more than they had to. Workers turned management’s thrift into a weakness. Ordinarily if the (overwhelmingly male) staff needed to urinate, they’d simply go on the tracks. However when management tried to stop the job-and-knock system, workers decided they’d have to use an actual toilet.

The toilet could be a good distance from the actual point of work out on the tracks, which meant a long walk. Of course they had to be accompanied by the Protection Master. This then left the rest of the gang without protection, so they’d have to come along too. The whole gang would therefore traipse to the toilet and back, only to return and have someone else realise they ‘needed’ to go too!

The piss strike proved remarkably effective, with very little work getting done. Alongside the other work-to-rules, this had almost the effectiveness of a strike - but without the loss of pay and without the risk of being sacked for taking unofficial action in breach of contract. It forced management to completely cave in within two days, and the attempt to end the job-and-knock system was shelved. Andy comments:

“This all happened on the first night, the council couldn’t organise it, it came spontaneously from the mass meeting. That was the biggest non-RMT, non-PPP dispute we had – and the council wasn’t really needed!”

The Workmates legacy

While the delegate council had proved useful for raising smaller grievances when confidentiality was an issue, it had been sidelined by action organised directly from the mass meeting when a bigger dispute came along. By mid-2001, the delegate council had ceased to meet at all. Partly this reflected the waning of the wider anti-PPP struggle (PPP was finally introduced in 2003). It also reflected the fact that some of the guys who had been on the council got promoted into roles with more responsibility. They didn’t become managers, but got a few more responsibilities in return for small pay rises. This wasn’t a deliberate move on management’s part, however, as they were unaware of the council and its role.

“The management didn’t really know about the council, it was all done in secret. They might have had an idea, but didn’t know details – it was the membership that knew. So with that, it meant they [some council organisers] weren’t able to come to meetings because they were getting their jobs ready, getting their tools together and stuff like that. So there were a whole number of issues and the council just kind of petered out. But we still had the Workmates mass meetings in the canteen fairly regularly, probably one a month, and they’re still running in the same manner.”

“It was an amalgam of things. Turnover, people moving on, me being too busy to put in loads of effort, and just a whole load of things. But I think it’s also a natural thing – I think it’s well recognised that these kind of things have a lifespan and then they kind of dwindle off. So, for a while I was really racking my brains about what to do about it dwindling, but now I’ve come to see it a bit more philosophically than I did then. Fundamentally we’re still operating in that manner, we just haven’t got the council.”

The culture of open mass meetings is perhaps the most significant legacy of Workmates. These both give mandates to RMT reps and hold them to account, as well as helping to overcome divisions between permanent and casual staff. This persisted even after the PPP went ahead in 2003 and track maintenance workers were all outsourced to the private firm Metronet. A good example of this was in 2007, when one group of contractors got farmed out to a line maintenance company on the Victoria line. RMT staff were in a wage dispute, and again some union members from the permanent staff crossed picket lines.

“Some of the guys who were in the gangs and were full time staff – in the union, and the wage dispute was for them, came into work. But the contractors who came from our depot, the ones who came in from Wales, they refused to cross the picket line. This was in a dispute that wasn’t going to benefit them in any way, they weren’t in the union and didn’t work for the company. So the solidarity is still there.”

The following year in October 2008, Metronet management fitted up Andy on four bogus charges of gross misconduct and suspended him pending a hearing. Leaks from management suggested he was going to be fired in retaliation for his role in a September 2007 RMT dispute over plans to cut pensions by 10%. The struggle was successful and the cuts were shelved. Then in April 2008 outsourced Metronet workers in the RMT won admission onto the Transport for London (TfL) pension scheme, free travel on TfL and subsidised travel on Network Rail to new starters - all previously denied to them by Metronet.

This was a significant gain for the workers, both combating the creation of a two-tier workforce with different conditions for pre- and post-privatisation starters and significantly reducing the costs of commuting to work for all Metronet staff, the equivalent of a modest pay rise. But this cost the company and as a result the bosses sought to victimise Andy for his part in the dispute, having clearly made the judgement that the past militancy had waned sufficiently to get away with it. Andy was suspended for three weeks pending the hearing. A strike ballot across the RMT returned an overwhelming ‘yes’ vote to walk out – on the same day as a London-wide bus strike – if Andy was sacked.

A packed public meeting on the eve of his appeal went one further. The room, including many Workmates veterans, made it clear they wouldn’t wait for official action to commence before taking action if Andy was sacked. Metronet completely backed down, first giving Andy a one-year written warning instead of sacking him, and then suspending the warning the following day. Andy had little doubt that it was the widespread support amongst Metronet, TfL and contractor staff – and the credible threat of direct action that forced management to back down, something which was very much part of Workmates’ legacy.

Conclusions

The Workmates collective grew out of the anti-privatisation struggles that were going on in the late 1990s. In the end, these struggles failed to make a dent on the actions of London Underground. These defeats themselves came off the back of years of defeat since the Thatcher era. In the face of all this, it's easy to see why many felt the days of the organised workers' movement, with workers exercising power on the job was over.

However, as Workmates showed, it's not our power as workers that has decreased but the power of the trade unions, which have had difficulty adapting to the changes brought by neo-liberalism. This is because the trade unions are based on the assumption that a compromise can be achieved between workers and bosses. By channeling workers' anger, the trade unions offer the bosses stability in the workplace. To do this, unions recruit us by showing they can get benefits from management while at the same time showing management that they are the legitimate (and responsible) representatives of the workforce.

However, the increased use of casual, temp or agency workers on short term precarious contracts breaks this balancing act by removing the stability of membership from the unions. Workers leave jobs when short-term contracts finish, many are not employed directly by the companies they work for and some are even nominally 'self-employed'. Bosses are also less willing to compromise, so that the trade unions often have little to show for. This has led to a serious decline in union density in the UK and most countries in the Western world.

And how have the unions responded? Certainly not by taking the fight into the workplace! The unions solve their membership problem with ever increasing rounds of mergers: NALGO, NUPE and COHSE into Unison, AUT and NAFTHE into the UCU, TGWU and Amicus into Unite. The alphabet soup is dizzying to look at and no doubt we can expect more if membership continues to decline. These mergers take the focus of union activity further from the workplace and, as such, further disempower their ever-shrinking membership. Meanwhile, the official trade unions remain completely irrelevant to those outside of traditionally unionised industries (i.e. retail, hospitality etc) and those outsourced from traditionally unionised ones (such as the contractors discussed in this pamphlet).

However, as Workmates showed, this is the unions' problem and not necessarily ours. Actions like the 'piss strike' or the genuine threat of unofficial action after Andy had been sacked illustrate this perfectly. Workers are very capable of fighting and winning but our strength has to be based on structures controlled directly by us. When we hand control over to the official unions, we have to obey the bureaucrats and trade union legislation. Essentially, we end up fighting on the bosses' terms. But by taking action quickly, at the site of the problem and giving management no time to prepare, we can fight on our terms. And it's on our terms that we can win.

This leads us to another question: given that the official trade unions are so unfit for purpose, what can the workplace militant do? How should they relate to the official unions? Leaving the union (where there is one), in most cases, will simply leave militants in the wilderness, unable to make use of some of the valuable union resources. Equally, waiting for spontaneous militancy to arise from the workforce will leave radical workers waiting for a very long time as even 'spontaneous' action only looks so from afar – in reality, someone in the background always did the organising. Many militant workers are all too aware of the shortcomings of trade unions and wonder where this leaves them - a question of renewed urgency in an era of cuts.

Here too the Workmates experience shows us a way forward, because it illustrates that even just one worker with a serious commitment to independent workplace organising can get a lot done. By pushing for workers' organisation controlled by the workers' themselves, Andy put into practice an anarcho-syndicalist approach to workplace activity. Though the Workmates collective did not split from the RMT and form an independent union, it did make use of whatever union rights it wanted (like the ability of reps to consult with management) while maintaining enough independence so as not to be controlled by industrial relations law (as its willingness and ability to organise effective unofficial action showed).

However, as stated earlier, this does not mean we see Workmates as a blueprint for workers' organisation. Despite its successes, Workmates was not short of failings. The biggest shortcoming was probably the over-reliance on a small number of militants, with Andy playing a prominent role. The idea that organising is "the rep's job"- one of the legacies of trade unionism - makes it difficult to get workmates to share the load and to take collective control of the struggle . Andy reflects:

“It would’ve been better if I’d managed to do that more, and get more people to have an organising role without me having to be the person who does all the secretarial work. And when you’re doing secretarial work, what you’re really doing is organising people, you’re not just being a secretary who takes minutes and makes the tea or whatever – it is actually a leadership role. Because I was doing all the background work, I was always in a leadership position in a way. And I think if I’d found a way of avoiding that, it would have been good.”

Anarcho-syndicalists do not oppose leadership in itself, we oppose the role being monopolised by the same unaccountable people or institutionalised into union positions. In any struggle someone takes a lead by proposing ideas or pushing for action. However, any dependence on individuals poses both practical and political problems. Practically, it can lead to burnout as key activists get too knackered to carry on, or it can be neutralised by paying-off or sacking key organisers. Politically, it doesn’t prefigure the kind of free and equal society anarcho-syndicalists want to create, nor the kind of self-managed, fighting organisations we envisage will create such a society.

The failure to develop new militants put great strain on Andy, and ultimately independent workplace organisation itself. How to develop new militants is therefore an important, open question. Anarcho-syndicalists want to organise struggle in a way that develops new militants to supplement and take over from existing ones. This means finding ways to share the ‘administrative’ tasks of organising: photocopying, phoning/texting people, arranging meetings, winning co-workers round to the idea of direct action etc.

In the longer-term, however, this problem can only be solved by creating permanent organisational structures in the workplace: for anarcho-syndicalists, we see this as being the revolutionary union.

Class conflict is a permanent possibility in the workplace. The boss rules and we must obey. But this conflict rarely turns into action spontaneously. Only where there is some organisational presence (anarcho-syndicalist or otherwise) can management be challenged effectively. Where there is no organisational presence, attacks on conditions may provoke anger - but anger which all too often turns to despondency. And with each management attack, that despondence increases, creating a culture based on defeat, where ‘nothing can be done’.

Therefore anarcho-syndicalists aim to build a permanent organisational presence, based in the workplace, but from a clear revolutionary perspective as any workers' organisation not based on a principled rejection of capitalism will slowly slide into reformism and class collaboration. The goal of the revolutionary union is not to enrol every worker and then represent them to management. Its role is to organise and use mass meetings to include the whole workforce in struggles against the boss and to encourage workers to represent themselves, not be represented. Workmates provides one example of this kind of organising model in action.

Conditions in different workplaces, industries and countries will vary and so will the possibility of organising struggle. But no matter the conditions, militant workplace organisation cannot be achieved by political groupings organising outside of the workplace. So the revolutionary union is neither a political organisation nor an apolitical union concerned only with bread and butter economic disputes.

The revolutionary union does not just organise in the workplace but also in the communities we live in (such as the CNT in the Puerto Real shipyard strike of 1987). It seeks to be a permanent revolutionary presence that organises direct action, both to improve working class life in the here and now and to develop a culture of resistance within the working class.

As part of our efforts to form such an organisation, the Solidarity Federation is training and supporting workers who want to organise their workplace. We are committed to supporting workers organising regardless of whether they believe in every word of our constitution and regardless of whether they work somewhere with a permanent, fully-unionised workforce or in a completely precarious non-union job. If we are going to build a culture of resistance within our class we have to start with our everyday lives, where we live and where we work.

And as the Workmates experience shows, even one radical worker acting within a workplace can get a lot done. Using the unions when necessary but not relying on them; knowing the law but relying ultimately on direct action, solidarity and workers' control of struggle. This is the basis of anarcho-syndicalism.

Comments

Great pamphlet, I have